Jeff Padgett

Volunteer Lookout Host- St. Mary Lookout

Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness

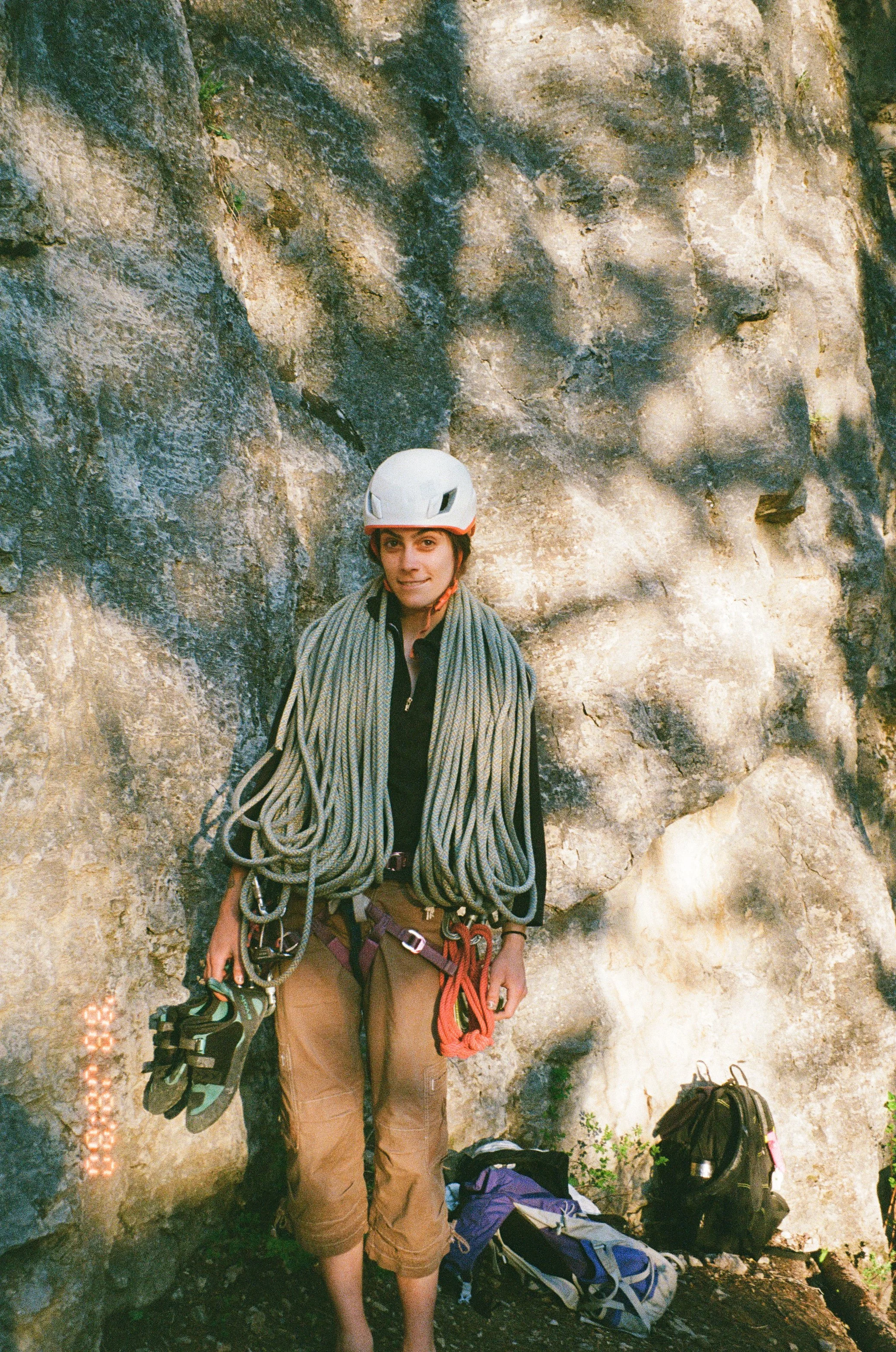

The author at St. Mary’s

I have been an SBFC volunteer at St. Mary Lookout near Stevensville, Montana for eight summers. There are two current volunteers who have been doing it longer than I have.

What causes volunteers like us to come back summer after summer? One rather obvious reason is that St. Mary, at 9351 feet on the eastern edge of the Bitterroot range, has one of the most expansive views in the Bitterroots. However, this year, I finally realized that another equally important reason for my circling back to St. Mary annually is the interesting and sometimes inspiring conversations that I have with visitors.

Anyone who knows me knows that I am a talker. I make a point of greeting each visitor to St. Mary as they reach the mountaintop. I sometimes miss a few on the busiest days, like Labor Day weekend, but I invite everyone that I do greet to come into the lookout. A substantial proportion take me up on my offer.

Most visitors ask questions such as: how long do I stay at the lookout (usually for two weeks, but one year I only volunteered for a week), where is Trapper Peak (the tallest mountain in the Bitterroots), where do you go to the bathroom (there is a viewful little perch on the southwestern side of the lookout, mostly concealed from view), what kind of wildlife do you see up here (personally, I have only seen elk, black bear, Clark’s nutcrackers and chipmunks), and so on. Perhaps with every 10th visitor or so (St. Mary gets 1500-2000 visitors in its approximately 8-week summer season), I engage in an extended conversation about all sorts of topics, which enriches my day and hopefully that of the visitor as well.

St. Mary Peak Lookout

Many visitors extend great kindness to me. Pretty much every season, someone brings me a beer (which I drink AFTER visiting hours). They are kept cool in a box that draws air from the basement of the lookout, and which keeps food cool as well. One visitor this year left me a sandwich and some beef jerky. I have had visitors bring fresh fruit (much appreciated), a packet of smoked salmon, and homemade cookies.

One little girl, Corinna, was with her dad. She was so excited to see the inside of a lookout. I don’t believe that many visitors to St. Mary have been in a lookout before. A lookout has been on the top of St. Mary since 1934. After 1977, the US Forest Service quit staffing St. Mary regularly. So for many years, people would trek up the mountain, and if they had chosen their day well, could soak up the expansive view to which I referred earlier. However, the lookout may or may not have been staffed and open to the public.

Here’s where SBFC steps in. At some point in the early 2010s, SBFC decided to sponsor volunteers to stay in the lookout at St. Mary for either one or two weeks. As a condition of opening the lookout, the USFS required SBFC volunteers to actively look to spot fires and to expeditiously report any that we do spot. However, if there are no fires in our viewshed, we are to greet visitors, welcome them to the lookout, and answer any questions that they might have. This allowed Corinna and her dad to enter the lookout, and the world had one happier little girl.

One year during my stint, a couple came up with a group of about 6-8 others. They were wearing backpacks and hiking clothing, and the woman was carrying flowers. They were going to be married on St. Mary!! I let the bride-to-be use the lookout as her dressing room. Her mother, who was from Indiana, had never hiked to a 9000-foot elevation in her life, but she said she wasn’t going to miss her daughter’s wedding! They aren’t even the first to be married on St. Mary. I’ve had another couple come up to the lookout on the anniversary of their marriage on St. Mary.

This year, a man brought his father’s ashes to the summit. An 80-year-old man recovering from shoulder surgery came up and we had an extended conversation about aging (I am 68). He has hiked the Appalachian Trail. I am currently in my third year of hiking the Pacific Crest Trail in approximately 500-mile segments. We spoke of the importance of squeezing all of the enjoyment possible out of life while we still have the health and mobility to do so.

Many times, the conversation with visitors turns to a spiritual topic. I think that mountaintops bring that out in people, a sense of continuity in a transient world. St. Mary isn’t special in that regard. The ocean, the Grand Canyon, or a dark night sky full of stars evoke the same sentiment. People climb a mountain to experience something different from their everyday existence. A mountain gives them a spot to contemplate their place in the universe. It centers them and gives them a sense of peace, allowing them to face another day in a world that sometimes seems on the verge of falling apart.

I firmly believe that trail maintenance should be SBFC’s primary mission. A cleared trail permits access to a quiet natural realm where the hum of mankind quiets. Yet I am grateful, as an SBFC volunteer and donor, that SBFC has had the courage and insight to try different avenues to allow its public to access the tranquility of the natural world. I believe that opening and staffing St. Mary lookout has been a public good. That is really my main reason for writing this “Tale from the Tower”.

Thank you, SBFC!

Jeff Padgett is an SBFC volunteer from Missoula, MT.